Takeaways

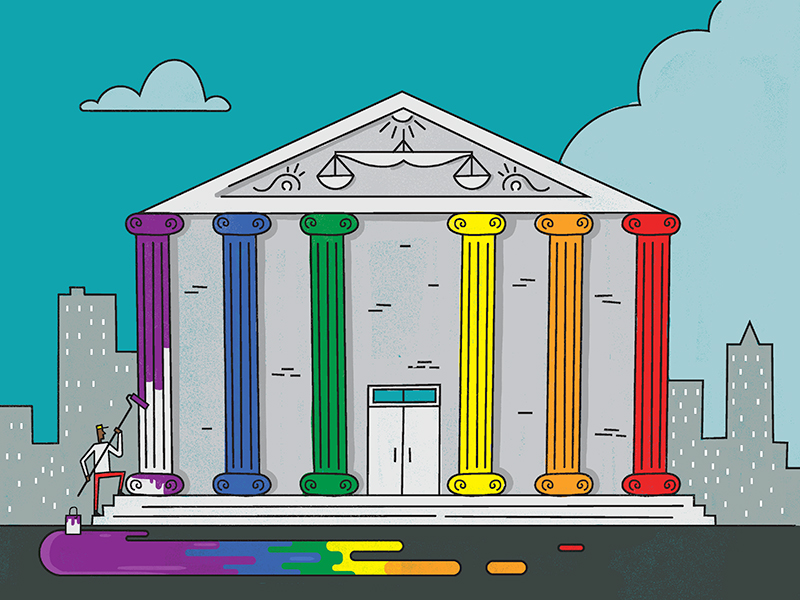

- Lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender workers have had mixed success using the 1964 Civil Rights Act to file discrimination lawsuits.

- The U.S. Supreme Court could provide a definitive answer this year about how LGBT individuals should fight discrimination in the workplace.

- The current patchwork of legal protections is not a viable option for major corporations to manage human resources.

The U.S. Supreme Court plans to hear three job discrimination cases this year brought by lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender workers and rule on whether the federal civil rights law protects those individuals.

Employers could receive more clarity for creating inclusive employment policies, but a recent paper by a Terry College of Business legal studies professor says one of the theories being advanced under the 1964 act is the least persuasive argument and most likely to be rejected by the courts.

No federal law explicitly protects LGBT people from discrimination.

“LGBT persons have been bringing court cases trying to argue that they’re protected under the Civil Rights Act of 1964 ever since the ’80s. It’s taken about 40 years to get this issue in front of the Supreme Court,” said Alex Reed, associate professor and director of the Legal Studies Certificate Program. “It seems to be receiving the most attention I’ve ever seen.”

Tangible costs associated with LGBT job discrimination cases include attorney’s fees, settlements and jury awards, while Reed identified a host of less tangible costs, ranging from decreased job satisfaction to damaging public relations and loss of LGBT customers, who have an estimated $3.7 trillion in purchasing power, according to LGBT Capital.

“This really is a business issue. For companies adopting LGBT-inclusive employment policies, they enjoy a significant advantage in the marketplace. There is a strong economic and financial rationale for adopting policies that protect LGBT workers,” Reed said.

In a 2015 decision, the U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission held that discrimination on the basis of sexual orientation constitutes sex discrimination. Because sex discrimination is prohibited under federal law, lesbian, gay and bisexual persons can evoke the Civil Rights Act to challenge an employer.

In his paper, Reed examined the feasibility of contesting sexual orientation-based employment discrimination on the federal level via the “sex” prong of Title VII.

There are three legal paths that LGB plaintiffs can follow to prove that the conduct constituted unlawful sex discrimination:

- “But-for” discrimination involves mistreatment that would not have occurred “but for” the individual’s sex.

- “Gender-stereotyping” discrimination confronts the bias that physical and emotional attraction should only be to persons of the opposite sex.

- “Associational” discrimination addresses prejudice based on the sex of the persons with whom the individual associates.

The last of those was the focus of Reed’s recent research article, “Associational Discrimination Theory & Sexual Orientation-Based Employment Bias,” published in the University of Pennsylvania Journal of Business Law in 2018.

He expects the plaintiffs in the two sexual orientation cases pending before the Supreme Court to rely on the associational discrimination approach, because it has been endorsed by the EEOC.

But the associational discrimination argument should be abandoned in favor of the “but-for” and “gender-stereotyping” routes. That argument is flawed and least likely to convince a judge to rule in favor of the employee, Reed found.

The reasons include that the Supreme Court has never recognized the validity of associational discrimination theory. Associational discrimination is also “under-inclusive,” he found, because most cases have focused on an intimate association with the other person. In addition, LGB plaintiffs would have difficulty establishing a prima facie case of discrimination under Supreme Court precedent.

Statutory efforts to prohibit sexual orientation-based employment discrimination have been underway in Congress and discussed in judicial and academic circles.

Reed said about 20 bills over 45 years have been proposed in Congress to protect lesbian, gay, bisexual, and now transgender, persons from employment-based discrimination. The current Equality Act bill in Congress has been endorsed by more than 215 major U.S. employers — including Apple, Amazon, Kellogg, MasterCard, Pfizer and Twitter — that employ more than 10 million workers in the U.S. and generate $4.7 trillion in revenue.

“It is now seemingly reaching peak interest because the Supreme Court agreed to decide this issue once and for all,” Reed said.

The state level is a patchwork of different protections for LGBT workers. Currently, 21 of 50 states have fully inclusive LGBT employment laws. They include California, New Jersey, Oregon and Utah. Workers in 29 states, including Georgia, Florida and Texas, have neither state nor explicit federal protection, Reed said.

“You’re seeing the business community at the forefront of this issue, really driving Congress and state legislatures to act because they recognize that this is a business imperative,” he said. “The current patchwork of protections is just not viable in terms of human resources management.”